Chinese dominance in Cambodia beginning to unfold

China is in full flow in Cambodia and every footprint of foreign looks what the Chinese government would like to see. China has pushed US, Japan and Singapore and Taiwan as Cambodia’s prime investors. It is all China but there is a simmering crisis fast emerging as per IMF data Cambodia could very soon be a defaulter under the burden of Chinese debt which has got high interest rates and go bankrupt like Greece.

Chinese investment in Cambodia has created a lot of employment opportunities. The Council for the Development of Cambodia says China has been the biggest source of foreign direct investment since 2011, with the cumulative total during the period until early December reaching $4.9 billion. New buildings are going up seemingly everywhere, and the bulk are being funded with Chinese money.

One of the most notable projects is One Park, or Phnom Penh No. 1, as the commercial and residential complex is called in Chinese. Heading the undertaking is Graticity Real Estate Development, a lesser-known developer based in Beijing. The first phase is being built on 7.9 hectares of reclaimed land once covered by Boeung Kak Lake.

The total cost of the project is unknown, but the construction fees alone will amount to $130 million, according to the state-owned China State Construction Engineering Corp, who won the contract. Another 11.1 hectares of reclaimed land has been set aside for further development.

The changing skyline may draw the most attention, but Chinese investment in Cambodia goes far beyond real estate.

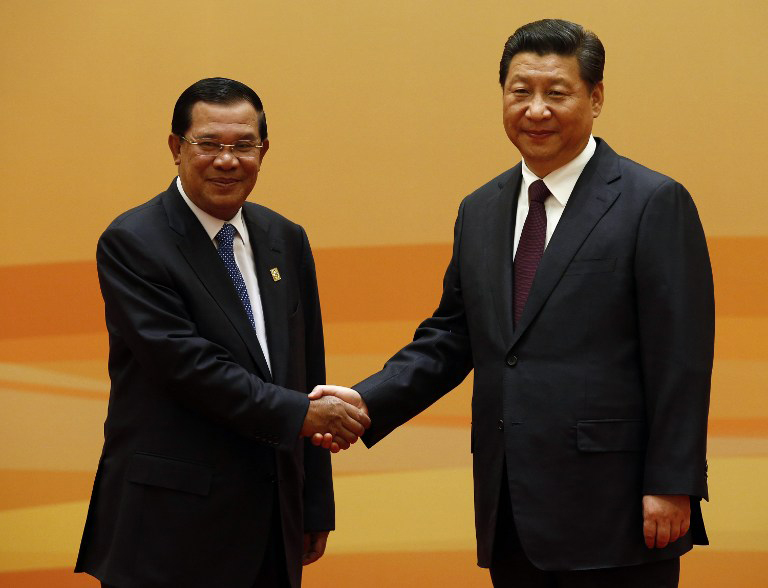

On March 6, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia Xiong Bo sat on separate construction vehicles in Phnom Penh.

The officials, along with about 600 locals, were at the groundbreaking ceremony for the western portion of the No. 2 ring road project.

This scene has played out countless times across the country, with the prime minister and Chinese ambassador on hand to celebrate the completion of new roads, bridges and other projects supported by Beijing.

“Thanks for all the assistance,” Hun Sen told a business delegation from China. “I can say that fraternal friend China has helped build the longest road, approximately 1,500km long, and seven bridges totaling approximately 3,104 meters long,” he said.

As bridges go, the New Chroy Changvar Bridge, completed in 2015 with a concessional loan from China, is packed with symbolism. The 719-meter bridge, which spans the Tonle Sap River in the capital, was built by the state-owned China Road and Bridge Corp. and runs alongside the Chroy Changvar Bridge, also called the Cambodia-Japan Friendship Bridge, built with Japanese assistance in 1966 and rebuilt with Japanese donations in 1994.

Tokyo used to be a major donor to Cambodia, but it now pales in comparison to Beijing. According to Moody’s Investors Service, China has since 2012 surpassed all multilateral organizations combined and the European Union in annual aid to the Southeast Asian country.

China’s presence in Cambodia’s power industry is also growing. The official website of the Chinese Embassy in Cambodia states that Chinese companies provided around 80% of all the power generated in the country in 2016.

The local Chinese Chamber of Commerce, which acts at the behest of Beijing, kicked off a two-week exhibit at the Royal University of Phnom Penh on Feb. 16 under the perfunctory title “achievements of electric power construction in Cambodia assisted by Chinese companies.” The aim apparently was to show off China’s economic muscle.

Chinese state news agency Xinhua said Cambodian Minister of Mines and Energy Suy Sem, who attended the event, thanked Beijing for investing about $2.4 billion in seven power plants over the past decade. Blackouts still happen, but they are less frequent now that the total electricity supply has surged from 180 megawatts in 2002 to over 2,000MW last year.

The stepped-up Chinese business activity is in line with Beijing’s overseas development initiative. “Make use of the successful visit by President Xi Jinping as a driving force,” Ambassador Xiong said at the annual conference of the local chamber of commerce last November.

He said companies should work to “deepen economic and trade relations” and “contribute proactively to solidify the economic basis of the full-fledged strategic alliance.”

The ambassador was referring to Xi’s first state visit to Phnom Penh last October. During the Chinese leader’s two-day stay, 31 official documents were signed.

The deals included debt waivers, a doubling of China’s import quota for Cambodian rice, the removal of double taxation and nearly $2 billion in infrastructure building. Cambodia is considered a crucial part of Xi’s pet project, the Belt and Road Initiative. Cash-strapped Cambodia, meanwhile, sees the plan as a way to build badly needed infrastructure.

Beijing also regards Cambodia as an indispensable part of its “string of pearls” maritime strategy connecting Hong Kong to Sudan via the Indian Ocean. Sihanoukville, the largest Cambodian seaport, is one of the pearls along the string.

Taking a cue from Beijing, Chinese companies are arriving in growing numbers. China Minsheng Investment Group led a delegation of over 100 companies to Cambodia in December. Its chairman, Dong Wenbiao, pledged to invest in an industrial park on the outskirts of Phnom Penh and set up an infrastructure fund worth several hundred million dollars.

On paper, the company is a private entity. But scratch the surface and the state connections appear. Its major shareholders include member companies of the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce. While the federation is a business organization, it receives guidance from the Unified Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, whose main role is to bring various sectors under the party’s umbrella.

In downtown Phnom Penh, the showroom-cum-sales office for the Sino Plaza, one of the largest Chinese development projects, suddenly closed without notice in the end of February.

Last January, a high-profile announcement boasted how the China Center-as it is called in Chinese-will consist of a hotel, condominium, commercial space and a theater, spread across over 13,000 sq. meters of land. The construction costs alone were billed as totaling $240 million.

The closure of the showroom sparked rumors that the project had run out of money or even gone bankrupt. Mary Thong-Lin, an administrative staff of the project’s main developer, Natural Lucky Real Estate Development, dismissed such talk as “all groundless rumors and lies.” Speaking with the Nikkei Asian Review on March 10, she said the building housing the showroom had a leaky roof and other problems and had to “go through repairs.” The groundwork for the complex was indeed underway, eye-witnessed by the Nikkei Asian Review, though she hinted that the original grand opening date of August 2019 may be pushed back. She did not say why.

Problems persist at the One Park megaproject, as its land rights have been caught in a lasting dispute that has seen the authorities crack down violently on local protesters. There have been a series of arrests and even imprisonments.

On Feb. 23, Tep Vanny, a local community representative and land activist, was sentenced to two and a half years in prison, as well as given heavy fines, for a protest she joined in 2013 to fight a forced eviction order from the Boeung Kak Lake area. Sixty-three local civil society groups issued a joint statement that day criticizing the police, parapolice and the military police for using violence to silence the former residents. The statement also condemned the court for handing down heavy sentences without credible evidence.

Naly Pilorge, deputy director of advocacy at one of the statement’s signatories-the Cambodian League for the Promotion & Defense of Human Rights-said the authorities are “once again punishing Vanny for her activism to send a clear message to any who dare criticize the government that dissent is not tolerated in Cambodia.”

What some see as an increasingly oppressive governance style is starting to alienate Western investors, a trend that only increases Cambodia’s reliance on China.

China is not offering Cambodia any free lunches. Along with a renewed emphasis on Beijing’s economic support for Phnom Penh, the joint communique signed by Xi Jinping and Hun Sen published last October stated that they have agreed to “further enhance coordination and cooperation within various multilateral frameworks” and to maintain close, timely and effective communications on matters concerning their significant interests to “offer forceful support for each other.”

In 2012, while serving as rotating chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Cambodia prevented the foreign ministers from issuing a joint communique for the first time in the bloc’s 45-year of history. The problem was due to wording over disputes in the South China Sea. Parroting China’s stance, Cambodia insisted that those maritime problems were bilateral issues and therefore did not have a place in a joint statement.

Since then, China’s influence on Cambodia has only grown stronger. More than ever, Beijing will expect the country to fall in line with its agenda.