Myanmar’s Rohingya crisis

A fresh outbreak of violence in Myanmar’s Rakhine state has caused hundreds of thousands of Rohingya civilians to flee to Bangladesh.

Tens of thousands of Rohingya are fleeing for their lives after an escalation of violence against them in Rakhine, the poorest state of Myanmar. A tide of displaced people are seeking refuge from atrocities-they are fleeing both on foot and by boat to Bangladesh.

Rejected by the country they call home and unwanted by its neighbours, the Rohingya are virtually stateless and have been fleeing Myanmar for decades.

More than 400,000 have fled from Rakhine to neighbouring Bangladesh amid a military crackdown, launched shortly after attack on police posts by Rohingya militants in the last week of August this year.

The military says its operations are aimed at rooting out terrorists and has repeatedly denied targeting civilians.

However, the Burmese military is widely accused of committing atrocities amounting to ethnic cleansing. They are accused of rapes, killings and house burnings, which the government of Myanmar has claimed are “false” and “distorted”.

Rohingya people are trying to escape violence, following a military counter-offensive against Rohingya militants who attacked police posts.

The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (Arsa) operates in Rakhine state in northern Myanmar, where the mostly-Muslim Rohingya people have faced persecution. The Myanmar government has denied them citizenship and sees them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

Clashes erupt periodically between ethnic groups but in the last year, an armed Rohingya insurgency has grown.

Those recent attack led to a security crackdown. Myanmar’s military says it is fighting insurgents but those who have fled say troops and Rakhine Buddhists are conducting a brutal campaign to drive them out.

Old saga

The Rohingya – a stateless mostly Muslim minority group – have faced years of persecution in Myanmar.

Tension between majority Buddhists and Rohingya in Rakhine state has simmered for years but it has exploded in violence several times over the past few years, as old prejudices have surfaced with the end of decades of military rule

Deep-seated tensions between them and the majority Buddhist population in Rakhine have led to deadly communal violence in the past.

Shortly after Myanmar’s independence from the British in 1948, the Union Citizenship Act was passed, defining which ethnicities could gain citizenship. The act, however, did allow those whose families had lived in Myanmar for at least two generations to apply for identity cards.

Rohingya were initially given such identification or even citizenship under the generational provision. During this time, several Rohingya also served in parliament.

After the 1962 military coup in Myanmar, things changed dramatically for the Rohingya. All citizens were required to obtain national registration cards. The Rohingya, however, were only given foreign identity cards, which limited the jobs and educational opportunities they could pursue and obtain.

In 1982, a new citizenship law was passed, which effectively rendered the Rohingya stateless. Under the law, Rohingya were again not recognised as one of the country’s 135 ethnic groups. The law established three levels of citizenship. In order to obtain the most basic level citizenship, there must be proof that the person’s family lived in Myanmar prior to 1948, as well as fluency in one of the national languages. Many Rohingya lack such paperwork because it was either unavailable or denied to them.

As a result of the law, their rights to study, work, travel, marry, practice their religion and access health services have been and continue to be restricted.

Myanmar’s government claims the Rohingya are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and denies them citizenship, even though many say they have been there for generations. Even Bangladesh also denies they are its citizens

Many are living in temporary camps after being forced from their villages by the wave of communal violence.

The predominantly Buddhist country has a long history of communal mistrust, which was allowed to simmer, and was at times exploited, under decades of military rule.

International response

The violence and the exodus of refugees has brought international condemnation and raised questions about the commitment of Government leader Aung San Suu Kyi to human rights, and prospects for Myanmar’s political and economic transition.

The UN human rights chief says rights violations in Rakhine have almost certainly contributed to the growth of Rohingya extremism.

The US has also called for the Myanmar military to end the violence and support diplomatic efforts for a long-term solution for the Rohingya, who are denied citizenship in a country where many Buddhists regard them as illegal immigrants.

It is one of the strongest US government response till date to the violence.

The US will provide a humanitarian aid package worth nearly $32 million to Rohingya who have fled violence in Myanmar’s Rakhine State in recent weeks

Even Rohingya’s have entered into India in large numbers and it has become a challenge for the government to handle them.

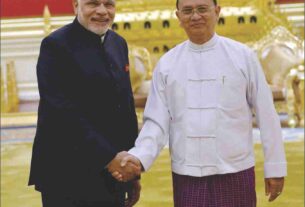

India is trying to maintain a balance between the contradictory interests of Myanmar and Bangladesh. It has its own reasons to worry about the onslaught of refugees. India fears radicalization of this group and there have already been some statements by Indian ministers calling for deportation of some 40,000 illegal Rohingya immigrants.

India’s has made plans to deport Rohingya Muslims who have escaped the violence against them and for this it is facing international condemnation.

“Like many other nations, India is concerned about illegal migrants, in particular, with the possibility that they could pose security challenges. Enforcing the laws should not be mistaken for lack of compassion”, said Permanent Representative of India to UN in Geneva Rajiv K Chander

Minister of State for Home Affairs Kiren Rijiju has said on this issue that India’s concern is sought to be justified on the grounds that these Rohingya population are susceptible to recruitment by terror groups, and that they not only infringe on the rights of Indian citizens but also pose grave security challenges. Also, he argued that the Rohingya must be deported to ensure the demographic pattern of India is not disturbed.

Refusing to bow under international pressure over Rohingya crisis, India has made it clear that it would not compromise with the security concerns of the country. However, the government has decided to extend help to Bangladesh in providing all amenities to the fleeing Rohingyas, who are being relocated in camps there. India has also asked Myanmar to end persecution of Rohingyas.

Bigger issues

The tragedy of the Rohingya is part of a bigger picture. The ethnic and religious issues are undeniable but few political and economic context too contribute which often go unnoticed. The Rakhine community as a whole feels culturally discriminated, economically exploited, and politically sidelined by the central government, which is dominated by ethnic Burmese. In this particular context, the Rohingyas are perceived by the Rakhine people as additional competitors for resources and a threat to their own identity, which is the main cause of tension in the state and has led to numerous armed conflicts between the two groups.

Furthermore, the Rakhines feel politically betrayed, as the Rohingyas do not vote for their parties. This has created more animosities between the two ethnic groups. The government, instead of fostering reconciliation, is supporting Rakhine Buddhist fundamentalists in order to safeguard its interests in the resource-rich state. These factors are the major reasons behind the rise of intercommunal, interethnic and interreligious conflicts, as well as the worsening of Rohingyas’ living conditions and socio-political rights in the state.

With no country willing to take responsibility for Rohingya, they are either forced or encouraged to continuously cross borders. The techniques used to encourage this movement have trapped the Rohingya in a vulnerable state.

A major change in approach is needed by the international community to stop this cycle of violence against the Rohingya. However, it will not be incorrect to say that the solution of the Rohingya issue lies in Myanmar only.

The situation of the Rohingya can be resolved domestically if the political will is there. It won’t be easy but it can be done.